Alan Turing’s school report reveals little of his genius

Items from codebreaker’s life and death go on display at Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

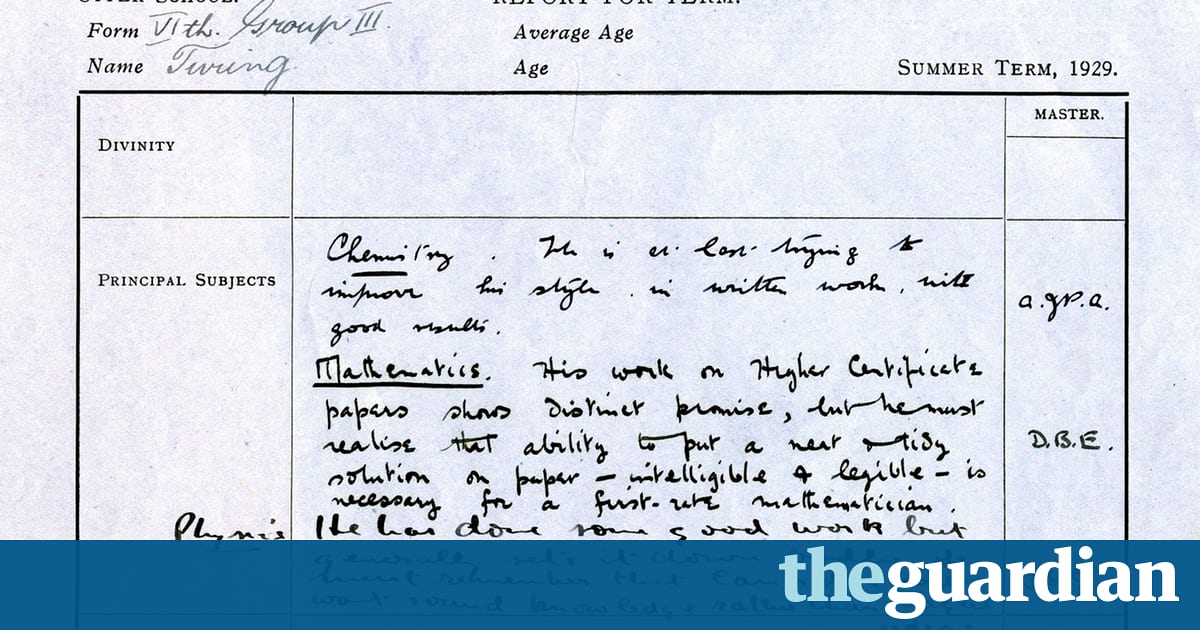

In 1929, a teenager’s end-of-term report noted that his English reading was weak, his French prose was very weak, his essays grandiose beyond his abilities, and his mathematical promise undermined by his untidy work.

The report gave few clues that Alan Turing would come to be seen as a genius, a mathematician and computer pioneer whose codebreaking work at Bletchley Park helped shorten the second world war and whose name is given to a test for artificial intelligence.

“He must remember that Cambridge will want sound knowledge rather than vague ideas,” his physics teacher wrote.

The report from Sherborne school is going on display for the first time this week, at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The Codebreakers and Groundbreakers exhibition also displays items borrowed from the government communications headquarters, GCHQ, such as a German coding machine and its British equivalent which the Germans never cracked.

The loans from the Turing archive include a science book which contained a chapter on codebreaking that he chose as a school prize in honour of his beloved friend Christopher Morcom, a brilliant pupil who died of tuberculosis aged 18. Turing won the prize for an experiment first demonstrated to him by Morcom.

A letter written to his mother from Bletchley Park, where he helped crack the German Enigma and other codes, describes his sponsorship of two Jewish refugee boys to come to Britain.

The exhibition contrasts the wartime codebreakers with their contemporaries who were working on deciphering Linear B inscriptions in Mycenaean Greek, the oldest writing system in Europe.

- Codebreakers and Groundbreakers is at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until 4 February 2018

“You may be a genius like Alan Turing, but if you lack writing skills, you are more likely to face a lot of academic troubles. Thus, a case study writing service can be of much use to easily handle your writing stuff.”