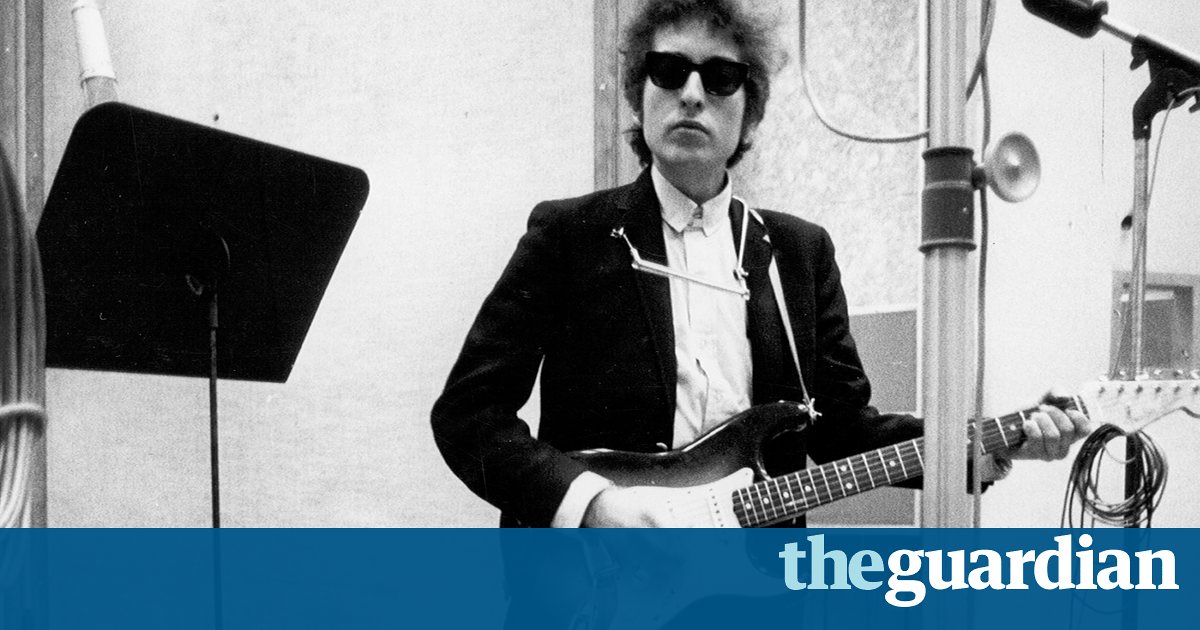

Fascinating, infuriating, enduring: Bob Dylan deserves his Nobel prize

Many have questioned the accolade, but there is no question that he is a singular talent even if he’s not really a poet.

As you will no doubt have noticed, Bob Dylan is the recipient of the 2016 Nobel prize for literature for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition. It is perhaps worth noting that several songwriters have, in their different ways, done just that since the prize was inaugurated back in 1901. Off the top of my head, here are just a few: Cole Porter, Chuck Berry, Carole King, Curtis Mayfield, Brian Wilson, Randy Newman, Paul Simon and, of course, Lennon and McCartney. As far as I know, none of them has ever been in contention for the prize.

As we have also saw last week, the very notion of a popular song, even a Bob Dylan song, being a work of literature remains a contested one. Likewise the notion of the songwriter as poet. It strikes me that the entire history of the Nobel prize for literature has been, until now, a refutation of these upstart notions. The times may indeed be a-changin, but it is difficult to see last weeks decision as a precedent: more as an exception.

Why might this be so? Of Dylans contemporaries, Leonard Cohen, who was an actual published poet before he embraced songwriting, could stake a claim to being more poetic in the literal sense, and thus more deserving of a literature prize. There is a case to be made, and I have made it, for Joni Mitchells musical and lyrical sophistication outstripping, for a time, that of her male counterparts, so she, too, is an obvious contender, but lets not hold our breath.

Dylan, though, occupies a singular and exalted place in the pop pantheon. He fascinates, he frustrates, but he endures; as does the myth of Dylan, despite all his attempts, to demolish it.

It was not always thus. Back when I belatedly purchased my first Dylan record in the early 1970s, glam rock and progressive rock were the two predominant pop genres, and Dylan was little more than a rumour. The record in question was John Wesley Harding (1967), which I bought solely because it was on sale at a reduced price that matched my meagre means.

For the uninitiated, it is an austere collection of songs with stripped-to-the-bone musical accompaniment, written almost 50 years ago, so the story goes, with the King James Bible and the songs of Hank Williams as its spirit guides.

Perhaps because it was my first encounter with Bob Dylan, it intrigues me still in a way that other much more groundbreaking and critically lauded Dylan albums do not. It seems a good place to begin to try to make sense of why the Nobel academy broke with tradition to canonise a songwriter rather than a novelist or dramatist.

Unbeknown to me when I first encountered it in the early seventies, John Wesley Harding was the first evidence of Dylans long retreat from his earlier era-defining music and his own mythology. The albums that followed it, from the wilfully perverse easy listening of Self Portrait (1970) to the mildly intriguing Planet Waves (1974), seemed designed, first and foremost, to confound the very idea of Bob Dylan. In retrospect, I was fortunate to begin my journey into Dylan with John Wesley Harding. Though pared down musically and lyrically, it is a record steeped in allusion, from the opening song, which makes reference to the radical 18th-century thinker, Tom Paine, to I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine, which remains, as far as I now, the only pop song to namecheck the controversial 4th-century Christian theologian.

John Wesley Harding was also, I later found out, the follow-up to Blonde on Blonde, a double album from May 1966 of baroque, hallucinatory songs that is now generally regarded as the creative apex of Dylans most fertile period. It began in March of the previous year with the electric surge of Subterranean Homesick Blues beat poetry tied to a Chuck Berry riff which opened Bringing It All Back Home like a statement of intent. In July, the astonishing six-minute single, Like a Rolling Stone, was issued, shortly followed by his explosive appearance as a dandy with a Stratocaster at the Newport folk festival. The world of pop had shifted on its axis. As the American music writer Greil Marcus has noted, Dylans creative momentum in this short, 16-month period ranks with the most intense outbreaks of 20th-century modernism.

In the debate inevitably fuelled by the Nobel prize about whether Dylan songs can be regarded as literature, one inevitably thinks of the sheer ambition of songs such as the insular, mysterious Visions of Johanna or the epic, 11-minute ballad, Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands. On them, Dylan went where no one had gone before or has gone since in terms of the pop song; 50 years on, they may still be the most forceful arguments in his favour. For me, though, the austere Dylan songs still cast a spell, and my other favourites include the haunting Tears of Rage and the faith-driven Every Grain of Sand, songs that seem as powerful in their rigour and restraint as the more extravagant outpourings from the mid-60s.

Back then, though, having stretched the pop song and himself almost to breaking point, Dylan had little option but to retreat and rethink. Where he went in the process was back, not just into Hank Williams and the Bible, but deeper into the tangled, darkly mysterious, still relatively unexplored, terrain of the traditional American folk song. The austere ballads on John Wesley Harding emerged out of the psychic clearing house that is The Basement Tapes (1975), the slew of songs that he recorded on primitive home equipment in Woodstock after his motorcycle crash. On The Basement Tapes Complete, remastered and finally released in their entirety in 2014, these old-sounding, wilfully primitive, often strange songs are the first unsteady, confusing steps on a voyage to rediscover and reinvent himself that continues to this day.

It is the singular nature of that voyage, I would like to think, that also guided the arbiters of the Nobel prize. What makes Dylan different is not just the quality of his best songs, but his insistence on aligning himself to an older, deeper songwriting tradition that precedes pop and exists as a historical continuum outside our current somewhat blurred notions of culture and entertainment. In his characteristically elusive sleeve notes to World Gone Wrong, an acoustic album of covers of old folk and blues songs from 1993, Dylan applies the word masterpiece to Broke Down Engine, a song by the great blues singer Blind Willie McTell, which he also describes as a song about trains, mystery … variations of human longing … revival … ambiguity.

This comes close to describing the mysterious place whose existence he has made it part of his lifes mission to alert us to: what Marcus memorably called the old weird America sketched out in so many traditional folk, blues and country ballads about heartbreak, longing, love, desire, obsession, death and murder. Dylan is drawing on a deep well even if, of late, the end results do not quite come close to the mystery and allusion of his older songs. For Dylan, it is the journeying itself that counts, as evinced by his constant, often perverse, live re-readings of classics from his back catalogue.