Google CEO Sundar Pichai: ‘I don’t know whether humans want change that fast’

From artificial intelligence to cheap smartphones, Google is on the frontline of technological development. But is it growing too big and moving too fast? A rare interview with Google’s boss.

When Sundar Pichai was growing up in Chennai, south-east India, he had to make regular trips to the hospital to pick up his mother’s blood-test results. It took an hour and 20 minutes by bus, and when he got there he would have to stand and queue for an hour, often to be told the results weren’t ready.

It took five years for his family to get their first rotary telephone, when Pichai was 12. It was a landmark moment. “It would take me 10 minutes to call the hospital, and maybe they’d tell me, ‘No, come back tomorrow,'” Pichai says. “We waited a long time to get a refrigerator, too, and I saw how my mom’s life changed: she didn’t need to cook every day, she could spend more time with us. So there is a side of me that has viscerally seen how technology can make a difference, and I still feel it. I feel the optimism and energy, and the moral imperative to accelerate that progress.”

[AdSense-A]

Now 45, Pichai is a tall, slight man whose voice is a soft harmony of Indian and American accents. Sitting in his office in a quiet corner of Google’s headquarters, in Mountain View, California, he speaks thoughtfully, often pausing to find the right phrase. The room houses a few pieces of designer furniture, and the requisite treadmill desk the perfect metaphor for the pace Pichai has to keep up with. Yet his is a disarmingly calm presence, a world away from the prevailing stereotype of the macho-genius tech CEO; when Pichai got the job, one Google employee was quoted as saying: “All the assholes have left.”

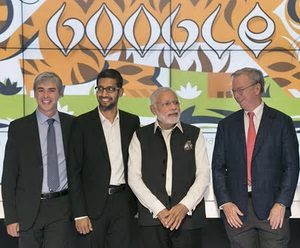

When Google restructured its sprawling business in 2015, it created a parent company, Alphabet, as a home for its more experimental projects space exploration, anti-mortality leaving its eye-wateringly lucrative consumer products with Google. Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, moved to Alphabet, leaving Pichai as the popular choice for CEO: he had already proved himself with his work on the web browser Chrome and Android, Google’s ubiquitous smartphone brand.

Compared with Page and Brin, and former CEO Eric Schmidt, Pichai is a modest and low-key figurehead. “I don’t do that many interviews,” he says as we sit down in his huddle meeting room. But the more we talk, the more it becomes clear that his appointment may be Googles shrewdest move yet: is he the perfect second generation chief exec? He certainly has a lot in his Gmail inbox. The catalogue of Google controversies is now so big it warrants its own Wikipedia entry, running from tax avoidance and anti-trust issues to hosting extremist content and recent claims of sexist employment practices (it currently faces a class action over pay discrimination).

Earlier this year, Pichai announced a major conceptual shift for the company, moving from mobile first to artificial intelligence [AI] first. This puts the focus firmly on machine learning, developing voice-recognition products such as Google Home, a smart speaker that responds to verbal requests to play music or control lighting; and, increasingly, visual recognition.

In an AI-first world, interactions become even more seamless and natural, Pichai explains. So, with voice, you can speak to things, and we are working on Google Lens, so your computer can see things the way you see them. Lens, due to launch later this year, will add visual recognition to smartphone cameras: point it at a restaurant, and it will find reviews online. Pichai also cites language translation as a compelling example of advanced AI; instant translation, both verbal and visual, will be possible with a high degree of accuracy within a few years, he says.

But this is where Google’s sell becomes tricky. Many developments in its services tailoring ads according to personal data, using someones location to present local information are viewed as invasions of privacy. The company has been the target of intense scrutiny on this score, particularly since 2013, when Edward Snowden revealed that the NSA and MI5 had been accessing personal information via technology companies.

With the application of AI, those concerns move into a whole new realm. In 2013, Google bought DeepMind, the powerful UK-founded AI company, with the aim of developing its capabilities further; but there are profound questions around the safety and ethics of creating machines that can think and act for themselves. Does Pichai acknowledge these concerns? “I recognise that, in the Valley, people are obsessed with the pace of technological change,” he says. “It’s tough to get that part right We rush sometimes, and can misfire for an average person. As humans, I don’t know whether we want change that fast I dont think we do.”

Another frequently raised concern is Google’s seemingly unstoppable growth: a year ago, it unveiled an initiative to reach the next billion smartphone users, targeting India with a handful of tools designed for mobiles with slow internet connections, including a version of YouTube.

“Isn’t this a kind of technological imperialism, bulldozing a way into the developing world? Pichai is prepared for this argument. I want this to be a global company,” he argues. “But it is also important that we are a local company; We don’t build only Google products and services we build an underlying platform, too, so that when you enable smartphones to work well in a country, you also bootstrap the entrepreneurial system there. The two go hand in hand.”

His ambition is to make Android so cheap that it can be used as part of a $30 smartphone; Pichai has said before that he can see a clear path to five billion users. “We want to democratise technology,” he says. “Once everybody has access to a computer and connectivity, then search works the same, whether you are a Nobel laureate or just a kid with a computer.”

***

By any measure, Pichai’s journey to the top of Google is a remarkable one. He was born into a modest middle-class family in Chennai, where he lived in a two-room apartment with his mother, a stenographer; father, an electrical engineer; and younger brother. The family had no car; sometimes all four of them would travel on the family moped. “Despite Pichai’s shyness, he was always confident and extremely determined,” says Professor Sanat Kumar Roy, who taught him for four years at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, where he studied metallurgical engineering: “I think he had some genius lurking in him.”

After graduating in 1993, Pichai won a scholarship for a masters in materials science at Stanford. His father, who earned 3,000 rupees (63) a month, withdrew nearly a years salary from the family savings to pay for his sons flight to San Francisco. “When I landed, my host family picked me up and driving back it looked so brown, he remembers. She corrected me: California is golden, not brown!”

He speaks of that time as a real culture shock, when he was grappling with his first experiences of computing. “I didn’t understand the internet. The change was too much for me. I think I was a little lost. But I felt the Valley was a special place. People would take me seriously for my ideas, not because of who I was or where I came from. It’s the remarkable thing about America we take for granted: that I could come and, after day one, my opinions mattered.”

After Stanford, Pichai worked at McKinsey and studied for an MBA, before joining Google in 2004. Two projects cemented his reputation within the organisation. Chrome, the now ubiquitous web browser, began as an experiment by his team of 10 engineers. He remembers the moment they got a prototype working, and realised it was pretty good.

But there was significant resistance: nobody wanted the challenge of taking on Microsoft’s mighty Internet Explorer. “Most people here didn’t want us to do a browser, so it was a little bit stealthy. Once we had it up and running, I remember showing it to Larry and Sergey and even then there was a lot of scepticism.” But Pichai got his way: Chrome was released in 2008 and now accounts for nearly 60% of the market, according to NetMarketShare, while Internet Explorer languishes on less than 16%.

Android, Google’s smartphone software, is now used by two billion people, but started as a small company bought by Google in 2005. In 2013, Android’s founder Andy Rubin was replaced by Pichai. With characteristic diplomacy, Pichai says now that the business needed a different approach. To do well and innovate, you need to have a construct by which people can work together, not built on individual people who are superstars.

Still, there is no denying that Pichai has had something of a superstar’s rise himself. Since becoming CEO, he has overseen seven products, each of them used by more than a billion people: Search, YouTube, Gmail, Chrome, Maps, Android and the Google Play Store, through which the company sells apps, music, movies and books.

Running a business that has more customers than the population of any country on Earth comes with its own unique headaches, namely a complex (and sometimes competing) range of geopolitical and social issues. The prospect of regulation is looming intensified by recent concern about political ads bought by the Russians to influence the US election. The European Commission last month levied a 2.2bn fine against Google for abusing its dominance in search advertising, and aims to push ahead with plans to force tech giants to pay more tax.

Against all these issues, Pichai pits Google’s willingness to look for collaborative solutions. He wearily explains the company’s position on tax; it became so synonymous with tax-efficient business practices that a 2015 levy on multinationals was dubbed the Google tax. “With tax, we would only argue for a more reasonable global tax structure,” he says. Is he suggesting that Google could and should pay more tax, if the loopholes were closed? That would be quite a contrast to Schmidt, who once said he was proudly capitalistic and insisted Google took advantage only of government incentives. Pichai neatly sidesteps this by citing the Paris climate agreement which, at least until recently, was an example of international collaboration: “It is super-important that humanity figures out more global cooperative frameworks to solve problems. No single company or country can change the pace of progress.”

In a speech to the UN in New York last month, Theresa May challenged technology firms to take more responsibility for their role in facilitating terrorist activity online, demanding they take down extremist content within two hours, the window in which it is usually shared the most. Isn’t it fair to insist a company such as Google shares responsibility for another unintended consequence of its vastly profitable success?

“She’s trying to address an important problem,” Pichai agrees, “and we should do better than we are doing today. The scale of these things is very difficult. In abstract, we have no disagreement, but the practicality is agreeing on a lot of important things.” These agreements led to an announcement in June that Google would add warnings and block ads from inflammatory videos, and would increase the use of both human and algorithmic moderators to flag and remove the most extreme videos. Within the context of its west coast libertarian ideology, Google also has to strike a difficult balance between allowing all parties freedom to express their views, while not facilitating terrorism. This could explain why, rather than speak more publicly about its policies, Google is choosing to partner with other tech firms, including one recent initiative with the UN counter-terrorism committee. Outsourcing the problem might make it feel slightly more comfortable for Google, which does not want to emphasise its geopolitical power.

Pichai says all the right things, but there is a fine line between thoughtful (the word his colleagues most often use to describe him) and evasive. Google has long had a tendency to avoid anything that looks like a political issue and simultaneously come to represent so many of the indulgences of the tech industry; even San Franciscos spate of protests against gentrification were targeted around Google, rather than the luxury commuter shuttles of all the other tech firms. “As a company, we end up being a symbol for many things, whether we want to or not,” Pichai says. “We have to hold ourselves to a much higher bar than everyone else. When we make mistakes it is very costly.”

Recently, he fired an engineer who wrote a controversial 10-page memo arguing against diversity initiatives, and claiming that the lack of women in tech was due to biological differences. James Damore outraged women at Google and the wider industry, and fired up the rightwing press, by claiming that Google employees with conservative views had to stay in the closet. One columnist argued that Pichai should be fired for not acknowledging the engineer’s concerns.

But while many critics seemed to view the decision to fire Damore as a statement about the right to free expression, Pichai viewed it as a workplace issue. “Obviously, you have an important right to freedom of speech, but you also have an equal right to work free of harassment and discrimination. When we talk about women in tech, our representation is around 20%. Nobody is trying to socially engineer anything [here] we are trying to solve hard problems. We were the first to publish our diversity numbers.”

In April, the US Department of Labor accused Google of systemic compensation disparities against women pretty much across the entire workforce. In September, a class action lawsuit was filed, alleging women were segregated into lower paying roles. “Any time you are in conflict with the government, you are never going to look good,” Pichai admits. “The overwhelmingly important thing is that we don’t have enough women in senior roles and higher-paying jobs. We are so committed to doing the right thing here, working on the underlying issues that prevent women from achieving their true potential. I feel very strongly about it.”

Jen Fitzpatrick started at Google as an intern in 1999. She is now vice-president of products and engineering, and has worked with Pichai since he joined the company in 2004. Like everyone I speak to at Google, she says he is widely respected for his thoughtfulness. “Sundar is unafraid to make tough calls,” Fitzpatrick says, “but before he makes that call, he makes sure he has heard from the right people across the company. He doesn’t make tough calls in isolation.”

Does he think some people in the Valley saw his appointment as a risk, given the prevailing culture? Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates all cultivated reputations for abrasive egotism, a convenient narrative that excused and even encouraged bad behaviour. In June, the tech industry’s most prominent bad boy, Uber’s former CEO Travis Kalanick, was pushed out of the company he co-founded after months of scandal.

“I’m not a fan of one story that tries to be archetypal,” Pichai says. He met Jobs, and doesn’t think enough is said about his more positive sides, his enthusiasm and drive. “I do think the Valley has good examples of leaders. Hewlett and Packard, who founded the Valley, built a company with a very strong set of values and were remarkably good to their people and partners. I never felt these things were at odds with each other. For the scale of Google, it is even more important to work well with others. In terms of a management philosophy, I try to find people not that they aren’t individually brilliant at what they do but people with the ability to transcend the work and work well with others.”

At home, Pichai describes himself as a news junkie who starts every day with an omelette, a cup of tea and a print copy of the Wall Street Journal. Back in India, where newspapers are omnipresent but expensive, he had to wait his turn until his grandfather and father had read the paper, though he did learn to negotiate for the cricket pages. He lives with his wife Anjali, whom he met at college, and their daughter, Kavya, and son, Kiran. He is familiar with the screen-time negotiation that goes on in most family homes, and used to restrict their time, but is now not so sure. “All of us are more comfortable when our kids read books,” he says, “but if they read on a Kindle, does that count? And what if the YouTube videos they watch are educational?”

“There are many extraordinary people at Google who would say they spent high school playing video games all the time,” he says. “Video games were how many people got into computer science, so a part of me thinks this generation of kids needs to deal with a new world.” Previous generations always feel uncomfortable with new technology. “In the Wright brothers era,” he points out, “there were serious newspaper opinion pieces worrying that bicycles would endanger young women, by enabling them to cycle away and escape. Our kids are also becoming better at dealing with visual information. But I’m not saying I have the answers. I struggle with it, too.”

In India he has become famous, and is mobbed wherever he goes. His story is the one every family dreams of: hard work and huge reward. Bigger egos might be tempted to exploit that popularity: would he ever return to India and move into politics? He looks slightly embarrassed and shifts in his seat. “I wouldn’t be any good at it; But I do want to go back to India and give back. I feel incredible support when I go there; it is humbling.”

When I ask how it feels to be in charge of Google, Pichai pauses and looks determinedly at the floor, then out of the window. History shows that the opposite of what people were worrying about is typically true. Go back 10 years and look at the largest market cap companies: the bigger you are, the more you may be at a disadvantage. He talks of the importance of creating small teams with limited resources, even within a company with 66,000 employees and a market value of $642bn. “As a big company, you are constantly trying to foolproof yourself against being big, because you see the advantage of being small, nimble and entrepreneurial. Pretty much every great thing gets started by a small team.”

It’s not lost on him that Google’s greatest threat could be its own success. And it is also revealing to have it confirmed that when you reach the top the biggest thing you worry about is sliding back down again. You always think there is someone in the Valley, working on something in a garage something that will be better.