How one woman harnessed people power to save old New York

New film tells story of Jane Jacobss battle’s against the wealthiest developers in the city.

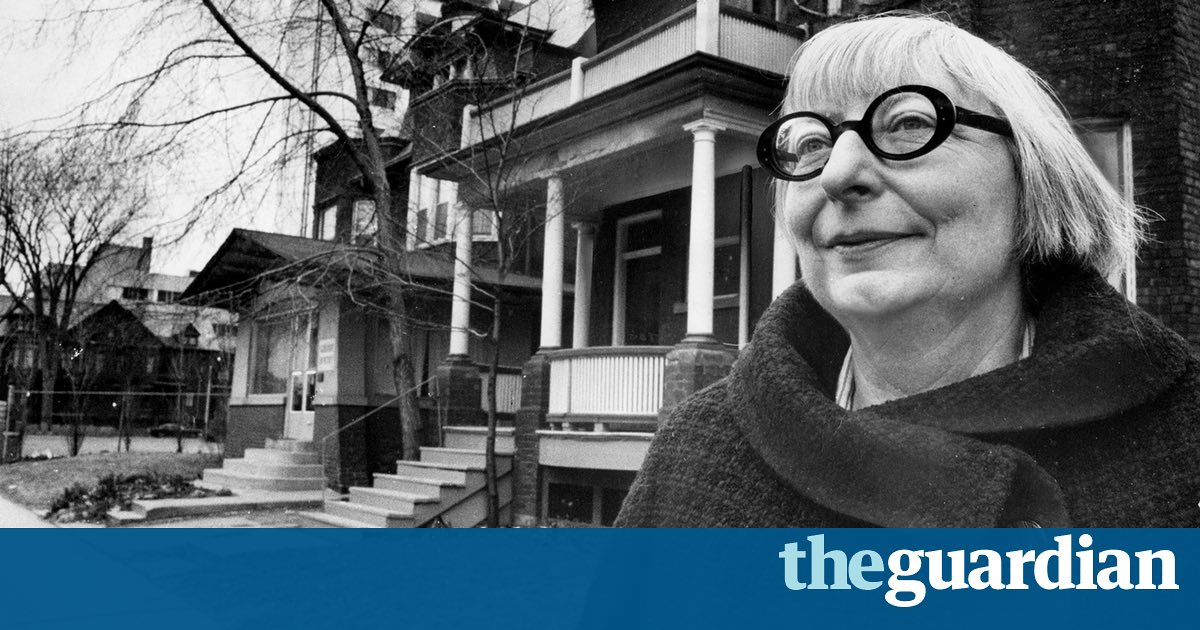

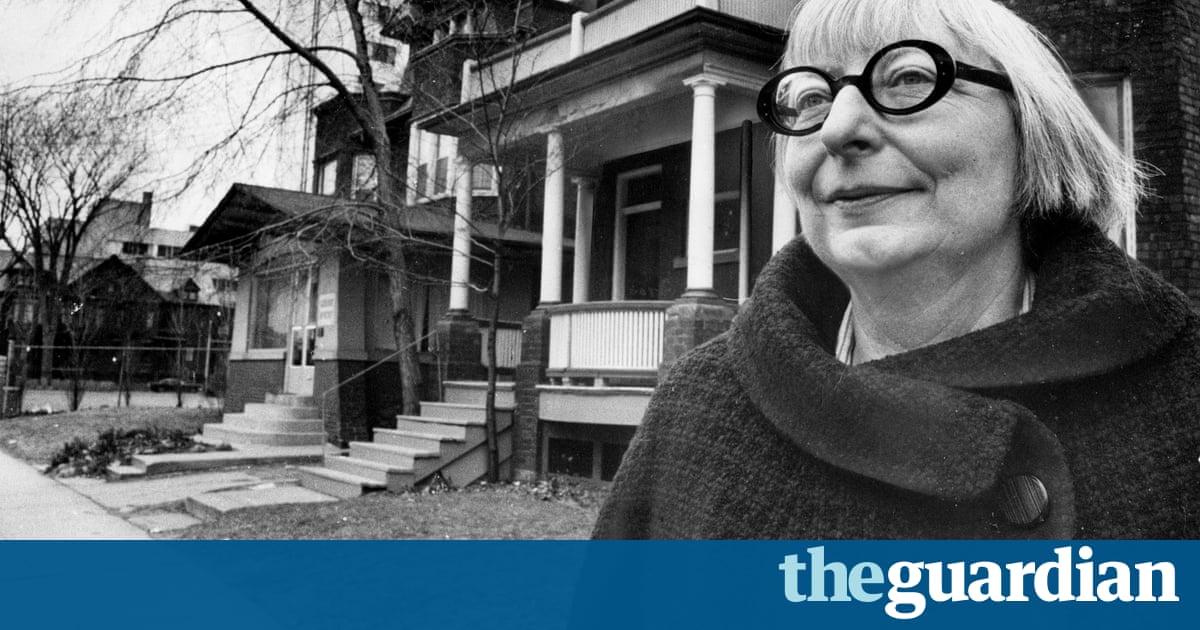

She was a beaky, bespectacled architecture writer, hardly a figure likely to ignite protests that changed the shape of one of the worlds great cities. Yet such is the legend of Jane Jacobs and her bitter struggles to preserve the heart of New York from modernisation that a film charting her astonishing victories over some of the most powerful developers in the US is set to inspire a new generation of urban activists around the world.

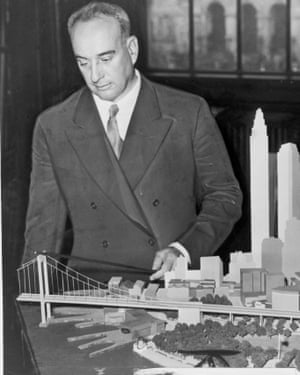

Citizen Jane: Battle for the City tells the story of Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, who made herself the bane of New Yorks powerful city planners from the 1950’s to 1970’s. Her nemesis was Robert Moses, the city’s powerful master builder and advocate of urban renewal, or wholesale neighbourhood clearance what author James Baldwin termed negro removal.

Moses dismissed the protesters as a bunch of mothers, and attempted to ignore their efforts to attract wider attention, which included taping white crosses across their glasses in the style of Jacobs.

But through a combination of grassroots activism, fundraising and persistence, Jacobs blocked Moses and successive city overlords from running Fifth Avenue through the historic Washington Square, tearing down much of SoHo and Little Italy to make way for a billion-dollar expressway, and building a six-lane highway up Manhattans west side.

“Some issues you fight with lawsuits and buy time that way,” she later wrote. “With others, you buy time by throwing other kinds of monkey wrenches in. You have to buy time in all these fights. The lawsuit is the more expensive way.”

Jacobs warned of the dangers of mixing big business and government, and called them monstrous hybrids. She warned, too, that huge housing projects favoured by developers from the school of Le Corbusier would only bring social dislocation to the poor while making developers wealthy.

Jacobs’s method of prevarication, says Citizen Jane director Matt Tyrnauer, wrote the manual for activism. Speaking truth to power was her great strength, and she was fearless, but she was also a great strategist and analysed how to get to politicians and threaten them in ways that were going to be effective.

Robert Hammond, who produced Citizen Jane and co-founded the High Line, a significant renewal project along Manhattan’s west side that turned an elevated rail track into a garden and walkway, says key to her protest was targeting lower-tier elected officials because they depend on you for their jobs and they know it. She understood that fighting government is a slog, and no matter how powerful you think people are, things can be changed the value of individuals coming together and working as an organism, which today we call crowdsourcing.

Those lessons, in particular Jacobs’s later studies of economics, helped shape The Indivisible Project, an umbrella organisation for thousands of protest groups that have sprung up in the US in the aftermath of the presidential election.

Tyrnauer, who previously directed Valentino: The Last Emperor, considers that Indivisible’s activism, which includes berating local officials and challenging congressional leaders at town hall meetings, is cut from the Jacobs playbook. Late last year the group’s founders, four congressional aides moved to act by the election of Donald Trump, published suggestions that have become central to democratic resistance. Six thousand groups have registered so far, seeking to follow Indivisible’s basic, Jacobs-esque credo: localised defensive advocacy; recognition that elected representatives think primarily about re-election and how to use that; efforts to build constituent power through organically formed, locally led groups; and a focus on congressional representatives via town hall meetings, district office visits and mass phone calls.

In her academic and personal life, Jacobs looked at the power individuals have in their own communities, says co-founder and executive director Ezra Levin. Indivisible is fundamentally about constituent power, and we recommend that people assert that power on their own turf, in their own communities. But the connection runs deeper. Jacobs maintained cities are best left to be self-organising. Too much control and they become lifeless. She believed they should be messy something old, something new and warned of the concentration of money and too little diversity. Crucial to Indivisible’s success is an individual group’s basic autonomy. “It’s crucial that this is not a franchise operation. We’ve created a platform but the decisions these groups are taking, or their exact form is fundamentally driven at a local level.”

Jacobs, who died in 2006 and whose centennial falls this year, used to tell an anti-authoritarian story about a preacher who warns children: In hell, there will be wailing and weeping and gnashing of teeth.

“What if you don’t have teeth?” one of the children asks.

Then teeth will be provided.

“That’s it the spirit of the designed city: teeth will be provided for you,” she told the New Yorker in 2004.

In Citizen Jane, the documentarians seek to apply the lessons of Manhattan in the 50’s to the urbanisation of China and India. The results are inconclusive.

Many of the challenges cities now face, at least in the west, are reversals of the clearances that affected cities in the last century. “The suburbs are where the poor people are moved to, and they’re becoming more impractical than cities to live in,” says Hammond.