The subversive genius of Joe Orton – BBC News

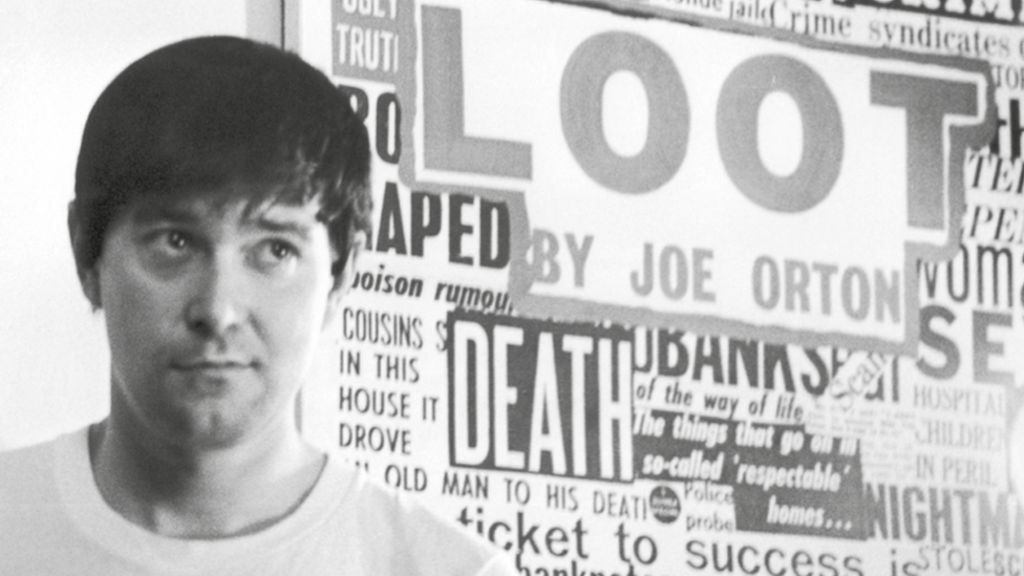

Fifty years ago the playwright Joe Orton was bludgeoned to death by his boyfriend at the peak of his career. What is Orton’s legacy, and what would he have made of the strides towards equality made since his death by gay people in the UK?

Riding high on the success of his latest play, Loot, and waiting for a chauffeur to ferry him to talks about a film he had written for The Beatles, the 34-year-old playwright was attacked as he slept by Kenneth Halliwell at the flat they shared in Islington. Halliwell, who feared Orton had been planning to leave him, then took a fatal overdose.

For Kenneth Cranham, the Olivier award-winning actor and friend of the couple, what happened on 9 August 1967 was hugely personal.

“I still had four grandparents then; I didn’t know anyone who had died. So to have one person that I knew so well die and another commit suicide was a living nightmare,” he said.

“Everything went into slow motion. In the play [Orton’s Loot was being performed at the time of his murder] you were running around with a body in your arms, there were coffins everywhere, and it was [supposed to be] a comedy.

“It was so bizarre.”

Born in 1933 as John Orton, he grew up with his three siblings on a Leicester estate typical of those built for workers in the 1920s.

His sister Leonie Orton Barnett has described their home as “drab, soulless and monotonous”, epitomising the “worst aspects of Leicester’s motto Semper Eadem – always the same”.

Orton, whose parents had an unhappy marriage, would leave his hometown at the earliest opportunity. He caught the acting bug in his teens and successfully auditioned for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (Rada) in London, moving there to study on a scholarship in 1951.

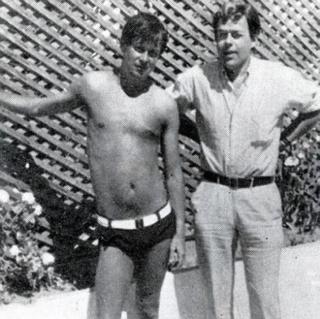

It was at Rada he encountered Halliwell, a troubled man seven years his senior.

“Meeting Halliwell was important because he found a collaborator with a shared sense of humour,” said Emma Parker, associate professor in post-war and contemporary literature at the University of Leicester, which houses the Joe Orton Archive and is running a series of events to mark the anniversary of his murder.

“Joe was reading Shakespeare and other writers before he got to London and met Halliwell, so it’s not fair to say he learned it all from him, [but] I think they were kindred spirits and they shared a sense of humour.”

After leaving Rada, they formed a writing partnership but had little success. The pair often went to bed at sunset to save money on electricity.

In 1962, a bizarre court case would land both men in prison – and ultimately provide the spark Orton needed to break though as a playwright.

The pair had spent more than a year altering library books with garish collages and occasionally obscene text, the targets ranging from biographies and volumes of Shakespeare to novels they viewed as low quality.

Their furtive campaign was eventually rumbled by zealous library staff and they were imprisoned for six months for theft and malicious damage, after a trial that attracted tabloid publicity. Orton believed the severity of the sentence was “because we were queers”.

Having gained a degree of separation from Halliwell, after his release Orton began to find success, with The Ruffian on the Stair broadcast on BBC radio in 1964.

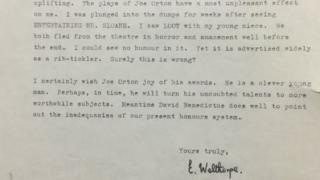

Entertaining Mr Sloane, a black comedy that touched on homosexuality and hypocrisy, was widely praised on its release, also in 1964, including by theatre heavyweights such as Terence Rattigan and Tennessee Williams.

The actor Dudley Sutton, who was part of the original cast, said he enjoyed being in a play “that was having a go at the established view of things”, and praised Orton’s sensitivity as a writer.

“He was so full of life, and I loved the dialogue,” he said in conversation with Dr Parker last year.

“To fight the demon of homophobia with a West End comedy was brilliant – I’m very proud to have been a part of it.”

Orton’s hallmarks as a playwright were black humour, deliberate bad taste, surreal situations and attacks on hypocrisy. His subversive nature helped him to stand out from his peers, with The Times describing Entertaining Mr Sloane as making “the blood boil more than any other British play in the last 10 years”.

For Bernard Greaves, a Cambridge architecture student in the mid-60s, Orton’s clear-eyed portrayal of aspects of contemporary gay life struck a chord.

“The impact of his plays was enormous,” he said.

“I didn’t have a large circle of gay friends at that time; I was in the closet living a double life – nearly everybody was, because it was still illegal – but Orton put on stage the reality of what it was like for us in an unvarnished way.”

For the playwright’s sister, Orton’s work helped pave the way for other gay men to be more confident in their sexuality.

“I think people who really understood the writing know that this was somebody original and unique,” Ms Orton Barnett said.

“He was so out there with his homosexuality, he was talking about it so frankly, and in such graphic detail, it brought a lot of people out.

“They’d say: ‘Joe Orton said it’s allowed, so I think it’s allowed’, and he was so right in being so direct about things.

“I think Joe liked the idea of it being unacceptable, he liked that idea of him being a rebel and being outside of society.”

Just weeks before his death, the Sexual Offences Act, which decriminalised private homosexual acts between gay men over the age of 21, was granted royal assent.

However, with the age limit higher than that for heterosexual sex, and with other restrictions still in place, Ms Orton-Barnett says her brother was not a supporter of the bill.

“I think he liked the mystique about homosexuality, he liked the closeted aspect,” she said.

“He wouldn’t have gone for the modern gay marriage at all.”

Dr Parker agrees, adding that Orton’s love of subversion underpins his plays and personality.

“He was kind of queer rather than gay – he liked weirdness and deviance, because ‘civilisation’ persecuted homosexuals and he thought it was barbaric and didn’t want any truck with it,” she said.

“It rejected him, and so he rejected it.

“I think his sexuality is really important to his writing and his worldview,” adds Dr Parker, who cites Orton as an influence on, among others, contemporary playwrights such as Martin McDonagh and Jez Butterworth, the novelists Jonathan Coe and Jake Arnott, and musicians including Morrissey and the Pet Shop Boys.

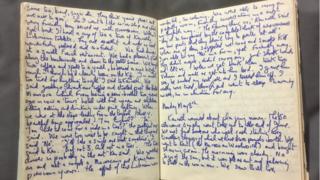

“He was a funny writer and full of life, but he was furious about society and sexual inequality; we know that from his diaries and his plays.”

Cranham – who said appearing in Ruffian on the Stair aged only 19 “completely changed everything for me” – played Hal in the 1966 West End production of Loot, Orton’s satire on the Catholic Church and attitudes to death. (Kenneth Williams had starred in the play’s initial, unsuccessful, run in Cambridge the year before.)

“Paul McCartney said that to him theatre meant a sore arse, but he wanted Loot to go on for longer,” the actor said.

“It shows Joe wrote plays for all people, and there was a connection between them and him.

“Joe always used to say he was from the gutter, but he just knew what real life was like.”

Orton’s star continued to rise after his death, with his final play What the Butler Saw – a farce that turns its guns on power and a psychiatric profession that treated homosexuality as a mental illness – becoming a stage success (although Up Against It, a film written for The Beatles, never reached the screen).

What the Butler Saw has been performed in Orton’s hometown to mark 50 years since his murder, and several revivals over the years have helped to maintain his status as an iconic figure in British theatre.

Ms Orton Barnett argues that her brother’s plays and posthumously published diaries give him a similar standing to some of the giants of literature.

“I always say the equivalent of Shakespeare in the 1960s was Harold Pinter, and Joe was the Christopher Marlowe – he died a violent death, but he was really important culturally,” she said.

“He didn’t conform at all – he always said that he writes the truth.”

For Cranham, who was among stars including Pinter and Donald Pleasance to attend Orton’s atheist funeral service, the playwright’s unerring brilliance as a writer of farcical satire remains a loss keenly felt by British theatre.

“I wish we could have known what would have happened to him as an older writer,” he said.

“He was a great writer, and could have done so much.”

Joe Orton, select bibliography

- The Ruffian on the Stair, radio play (1964)

- Entertaining Mr Sloane, stage play (1964)

- Loot, stage play (1965)

- The Erpingham Camp, television play (1966)

- The Good and Faithful Servant, one-act television play (filmed in 1967)

- Funeral Games, television play (1968)

- What the Butler Saw, stage play (1969)

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leicestershire-40511985