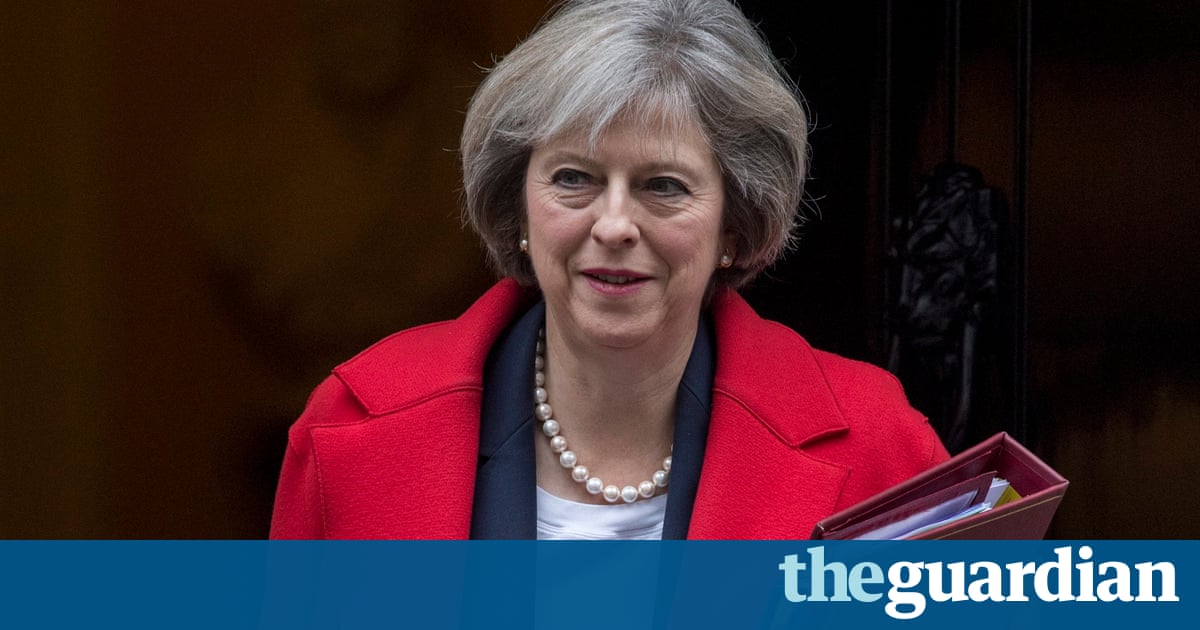

Theresa May must fight the hard Brexiters or Britain will be ruined | Will Hutton

The economic fallout from a violent rupture with the EU will have devastating consequences for the country and its people.

Brexit is pure poison, polluting everything it touches. The fundamental questions the country should be addressing the crisis in productivity growth, the lack of affordable housing, the overwhelming strain on public services, our desperately weak export sector are all sidelined. There is not the bandwith or capacity to address them against the gigantic question of how to weather the greatest shock to our economy and society since 1945.

Be in no doubt. Brexit transcends the 1974 oil shock or the 2008/9 financial crash in the probable scale, intensity and duration of its impact. Every aspect of our economy is going to be affected. Investment decisions are going to be abandoned or reduced.

Of course, there is a degree of uncertainty about how much of a shock it might be. Britain negotiating a custom-made deal that allows a well-managed transition to full participation of the single market would be less of a shock than a sharp, hard Brexit rupture, but it is not going to happen. Every time she hints at it, Theresa May gets beaten back by the powerful, Brexit faction that wants nothing less than rupture. She then retreats, judging that keeping her party together is more important than retaining some association with the EU. Unless and until it becomes obvious that hard Brexit is both avoidable and enormously self-damaging, there is no political coalition strong enough to resist it.

Last week, the Office for Budget Responsibility, recognising that the Brexit faction makes the political weather, buckled and declared that its best guess was that Brexit would only be a short-lived mini-shock. It still earned brickbats aplenty from the new bovver boys in British politics, but the OBR pulled its punches. Its economic forecast of a small slowdown in growth, before it is fully resumed in two or three years time, is an optimistic outlier. Even so, the impact is severe. The intense squeeze on spending on public services has to continue to give any hope of balancing the budget even if this aim has been necessarily deferred until early in the next decade. But the shortfall in tax revenues means there will, cumulatively, be another 58bn of public debt than there would otherwise have been.

Worse, the rise in inflation caused by the fall in the pound means that what peoples wages will buy so-called real wages are hardly going to rise at all in the years ahead. Indeed, the Institute for Fiscal Studies projects no rise for another five years, so that real wages will be below 2008 levels for 13 years. The Resolution Foundation points out that in every decade since the 1920s real wages have risen by 20%, slowing down in the 2000s and now set to grow by only 1.6% in the 2010s. Both bodies declare that there has been no economic pain on this scale for the mass of wage earners for more than 70 years.

The impact will be hardest felt by the bottom 30% of the population, most reliant on the welfare system, but a welfare system scaling back support, freezing most benefits in cash terms. Public and social housing provision is stagnating. There has been no period like this in modern British economic history.

All the risks are that it could even be worse. The OBR thinks that inflation will peak at 2.6%; other forecasters think inflation could rise to 4% before it falls. That judgment matters: the higher inflation is, the more intense the squeeze on all forms of cash spending wages, welfare payments and public spending in real terms and the greater the depressive effect on the economy.

Then there is the judgment on private investment. The OBR sees it as falling a little. It’s hard to imagine what substantial investment can be justified next year or in the following years. Apart from a small real rise in government infrastructure spending, every notch on the dial is negative and all the risks on the downside.

Yet we have to endure Brexiters insisting that anyone who analyses the future in these terms is a Bremoaner, talking the economy down. There is a legitimate argument about how bad things could get the OBR recognises that in the range of its forecasts but to pretend all is well is delusional. Philip Hammond has done well to allow himself the capacity to spend compensating funds on infrastructure and science, but it is small beer against the severity of the underlying trends.

The open question is how this is going to play out politically. Negotiating with national governments, the European parliament and European commission simultaneously, across so many complex issues and with so little core agreement in government, is close to impossible. As the uncertainty mounts and the talks become ever more deadlocked, so the economy will suffer more and the Brexiters will blame it all on Bremoaners and European governments for obstruction and standing in the way of the democratic will of the people. The parts of the country that will hurt most the old industrial heartlands and left-behind communities are those that voted Leave and they will be receptive to the message.

Meanwhile, little is being done or can be done to address the economy’s core weaknesses, which is the real source of their distress. The bitterness and distrust can only grow, fuelling an ever more destructive enmity between Leavers and Remainers. This is, without doubt, the greatest crisis through which I have lived in my adult life.

Theresa May knows she wants a long transition to a custom-made participation in the EU single market. In the absence of any opposition or leadership elsewhere, she has to start saying so and start facing down the Brexiters. Otherwise, not just the economics, but the politics may start to be unmanageable.

- Comments will open Sunday November 27

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/26/theresa-may-fight-brexiters-britain-ruined