Whodunnit and whowroteit: the strange case of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor

The real mystery of this 1930s cult thriller is not its murder, but the identity of its writer. So, asks Jonathan Coe, who was Cameron McCabe and what were the facts behind his fiction?

This extraordinary work of postmodern fakery from the golden age of detective fiction was last reprinted 30 years ago, and in the intervening decades has acquired a legendary status. Introducing the book to those who havent read it yet, without revealing too many of its various secrets, is not an easy task.

It would be a terrible breach of protocol, after all, to give away the ending of a mystery story; and yet it would be hard to decide, in any case, what the ending of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor actually is one of the books many peculiar qualities being that the enigmas surrounding it do not come to a halt on the final page.

In this novel, reality and fiction bleed into one another in the most disorientating way. Of course its on one of its levels a murder story, so I will not do anything so crass as to reveal the identity of the murderer; but the identity of the author which lay hidden for more than 30 years after publication is in some ways the central mystery, and the more intriguing one. There seems to have been no particularly feverish rush of speculation when the name Cameron McCabe appeared on the British crime-writing scene, for the first and last time, in 1937, even though several reviewers remarked on the unusual nature of his book.

It was enthusiastically reviewed by Ross McLaren and Herbert Read, who called it a detective story with a difference. Mention was made of the fact that the story did not proceed or indeed resolve according to the normal rules of detective fiction; that the authors name was also the name of the principal character, and that the concluding fifth of the book was in fact an epilogue, purportedly written by a journalist friend of the narrators, commenting on its literary qualities and setting it within the context of recent trends in crime writing.

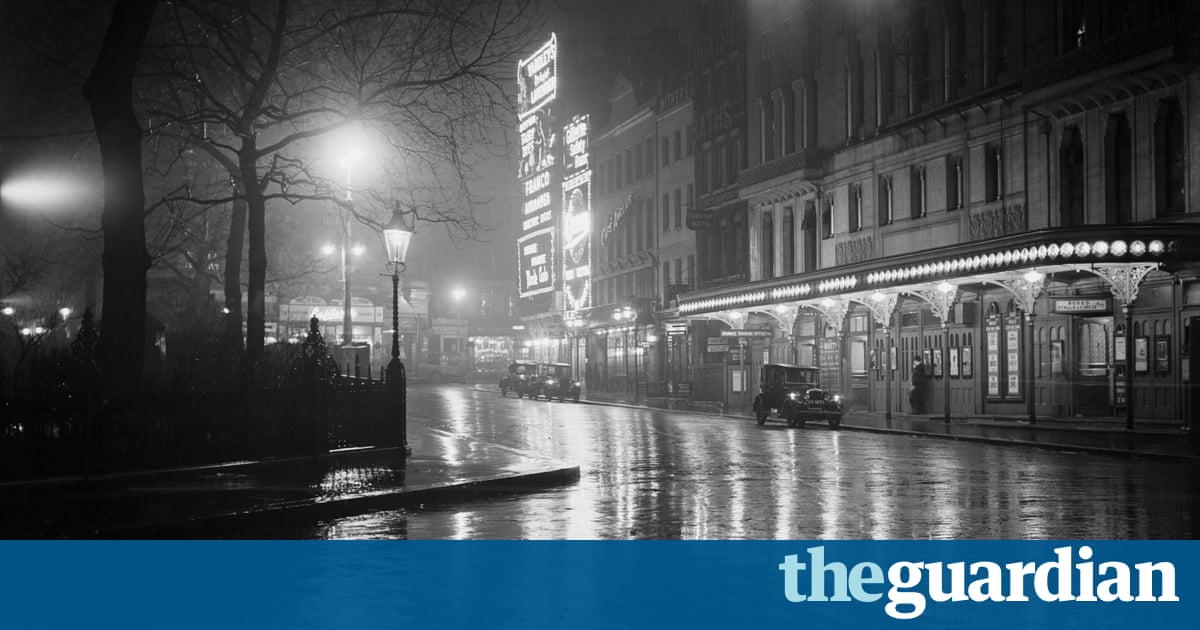

But just as much attention was focused on the story, which centres on an act of murder at an unnamed London film studio. An actor called Estella Lamare, already effectively killed off by a vindictive producer who has decided to excise her role completely from his latest picture, is found dead in the cutting room: her death has been captured on film by an automatic camera but the reel has gone missing. The subsequent investigation ranges from the streets around Kings Cross to the nightclubs of Soho, from tranquil, verdant Bloomsbury to the docks of the East End.

If Cameron McCabe was praised for the originality of his first entry into the crime genre, and for his novels strong sense of place, reviewers might have been surprised, and even more impressed, had they learned upon whom they were bestowing their acclaim. For the author of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor was only 22 years old when it was published and just four years earlier he had barely been able to speak a word of English.

His name was Ernst Wilhelm Julius Bornemann subsequently anglicized to Ernest Borneman and he had arrived in London as a communist refugee from Nazi Germany in 1933. In Berlin he had already made the acquaintance of Bertolt Brecht and worked for Wilhelm Reichs Socialist Association for Sexual Counselling and Research. Somewhere along the way, either in Germany or London or both, he also worked as a film editor and acquired a reputation as a virtuoso of the cutting room. Borneman was widely read in European literature and, once settled in London, wasted no time bringing himself up to speed with developments in English-language writing, discovering a particular affinity with Hemingway and Joyce, not to mention American crime writers such as Carroll John Daly and Dashiell Hammett. This presumably explains the distinctive, sometimes highly eccentric style of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor, which despite being set in an English film studio of the 1930s (which evokes images, perhaps, of genteel musical comedies performed in perfect RP accents), combines laconic, hardboiled dialogue with extended stream-of-consciousness passages, all filtered through the skewed phraseology of someone whose acquisition of English was still, to some extent, a work in progress.

Borneman was a man of formidable intelligence who, like many a postmodern writer before and after him, loved the narrative energies of crime fiction while wanting to remain aloof from its conventions and simplicities. This is the tension that explains, I think, the formal idiosyncrasies of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor.

It begins briskly enough, with a crisp, punchy dialogue between narrator McCabe and producer Bloom, followed by an important chance encounter with a stranger outside Kings Cross station, on one of those last evenings in November with the feel of July or August and the sky orange and heavy. We then get a long and evocative sequence following our hero on a nights adventures through bohemian Soho, and then there is the discovery of the murder itself, the next morning. After that, however, things start to get weird. You keep expecting the story to move forward and it doesnt, really.

Inspector Smith of Scotland Yard turns up to take over the case and we are drawn into a protracted battle of wills (alternately referred to as a fight and a game) between him and McCabe. The minutest details of the case who saw what, who was where and at what time are combed over again and again. Hardly any clues are offered, or deductions made. The story starts to become an exercise in reconciling different perceptions of the same event.

And then there is the epilogue. The idea of bringing in a (fictional) literary critic to offer an assessment of the manuscript doesnt exactly suggest that McCabe is a disciple of Dorothy L Sayers or Raymond Chandler: instead it calls to mind Alasdair Gray and his slippery creation Sidney Workman, who often pops up at the end of Grays novels to provide a commentary and footnotes. And when McCabes critic starts making general observations about the crime genre, such as The possibilities for alternative endings to any detective story are infinite, we are reminded that only two years separate The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor from that true masterpiece of early postmodernism, Flann OBriens At Swim-Two-Birds, whose opening paragraph concludes: One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with. A good book may have three openings entirely dissimilar and inter-related only in the prescience of the author, or for that matter one hundred times as many endings.

OBriens motives for undermining fictional conventions in this way are lofty and inscrutable. One senses only an amused Sternean scepticism about the whole silly business of writing books in the first place. With Borneman, though, the underlying aesthetic is more (forgive the pun) earnest. Given the fact that he knew Brecht while living in Berlin and came under the influence of his writing, I dont think its too fanciful to see some kind of Brechtian alienation technique being brought into play. Just as a later experimentalist, BS Johnson, would tear through the fabric of his novel Albert Angelo (by declaring Oh fuck all this lying!) in order to make a political point about the dishonesty of fiction, so Borneman here is drawing attention to the inadequacy of detective fiction to express the chaos, loose ends and ambiguities of real life.

This does not quite, however, make The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor the detective story to end all detective stories, as Julian Symons has claimed. For me, that accolade would have to go to Friedrich Drrenmatts The Pledge, published in 1958, at which time it bore the subtitle (later discarded) of Requiem auf den Kriminalroman or Requiem for the Detective Novel. Most of Drrenmatts book works superbly as a self-contained crime novella, and in fact the central story is a very faithful novelisation of his film script Es geschah am hellichten Tag (It Happened in Broad Daylight); but when turning it into a book, he also topped and tailed it with a framing narrative in which a writer of crime novels meets a cynical ex-detective in a bar, and after listening to his (true) version of the story, with its far less neat and satisfying conclusion, is left in no doubt as to the fatal short-comings of his own genre of writing. Drrenmatts forensic demonstration is elegant, devastating and final. By comparison The Face on the Cutting-Room Floors increasingly flummoxing layers of repetition and variation, and the elaborate metatextual apparatus at the end, feel more like a brilliant 19-year-olds roar of frustration at the limitations of the genre which he has chosen for himself.

And so, having apparently exhausted the possibilities of the detective story with his first book, what was Borneman to do next? Initially, at least, the matter was taken out of his own hands. As a German national living in the United Kingdom, not long after the outbreak of war he was apprehended and shipped off to an internment camp in northern Ontario. After a year of this, fortunately, his plight came to the attention of Sir Alexander Paterson, the British commissioner for prisons, who had met Borneman briefly in London, and recognised him when he came to Canada to inspect the camp. Paterson arranged for his release and put him in touch with John Grierson, who had also come to Canada to help set up the National Film Board. Before long, Borneman was working for the NFB in (where else?) the cutting room.

Graham MacInness memoir One Mans Documentary gives a vivid portrait of Borneman at work as a film editor. Watching him make sense of the vast mass of footage assembled for a naval documentary called Action Stations, MacInnes saw that this was someone with an eye as clinical and detached as a lizards, who approached his work with a fine mixture of Teutonic exactitude and a Jewish sense of extrovert lyricism.

To see his wavy blond head bent rigidly over a hand viewer; his strong but elegant hands ripping outs of film backward like gravel flung behind a bone-digging dog; his swift, frenzied but orderly snatching of takes from bins; his skilled manipulation, without getting them twisted or torn, of half a dozen shots; his mouth full of clips, his shirt-sleeved figure draped with film like a raised bronze statue with Aegean seaweed: this was to see a Laocoon writhing in the agony of creation. Borneman was a fanatic, a grammarian, a Central European engulfer and regurgitator of fact. But never a bore.

We are dealing with a remarkable man, then, obviously: and yet Ive barely begun to scratch the surface of his remarkableness. He was also, already, a leading authority on jazz (there is a lot of it in The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor) and his next publication was A Critic Looks at Jazz, a collection of journalism on the subject from his London days. He returned to Britain in 5the 1950s and worked as a jobbing screenwriter for TV shows such as The Adventures of Robin Hood. By now he had published two novels under his own name, Tremolo and Face the Music, a murder mystery set in the jazz world which was filmed in the UK in 1954. Another Borneman-scripted film from that year, Bang! Youre Dead, is a fascinating British thriller set in the world of villagers displaced and made homeless by German bombing, who still live in Nissen huts on an abandoned US army camp. In 1959 Borneman published Tomorrow Is Now, a cold war story described by the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum as evoking at times both Ibsen and Shaw, and which Borneman himself considered his best novel.

In the 1960s he returned to Germany, in an abortive attempt to set up a new state-funded TV channel and published his last two novels in English, The Compromisers and The Man Who Loved Women.

Finally Borneman settled in Upper Austria, where he lived in rural isolation in the village of Scharten. Isolation but not, by any means, obscurity: for now the final phase of his multifaceted career was under way, and he had made a considerable reputation for himself as an academic working in the field of human and particularly infant sexuality. By the time The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor was rediscovered and reissued in the early 70s, attracting extravagant praise from such writers as Symons and Frederic Raphael, Borneman was already the celebrated, sometimes notorious author of Lexikon der Liebe und Erotik and the monumental Das Patriarchat, which became a key text of the German womens movement. He continued to write, lecture and publish well into his 70s.

By the end of his life, Borneman had travelled an immense distance from his early, brilliant foray into detective fiction. Or had he? If we are to make sense of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor, in the end, perhaps we should see it, not as a postmodern intellectual prank, or a dazzling box of tricks, but as a work of wild and desperate youthful romanticism. By the time his part of the narration draws to a close, McCabe Bornemans alter ego has reached a suicidal frame of mind. Hopelessly in love with a woman who thinks nothing of him, he reflects that there is No way out for a man once a woman has got hold of him It will get you in the end.

In 1995, to mark his 80th birthday, Ein Luderlichtes Leben (A Wayward Life), a festschrift devoted to Bornemans life and work appeared, with a cover that showed him standing, fully clothed, next to a naked female model. The book had been compiled by a colleague of Bornemans, who was also his lover at the time. Before long, however, their affair was over, and in June of that year Borneman killed himself. It had got him in the end. It seems that the 22-year-old Cameron McCabe and the 80-year-old Ernst Wilhelm Julius Bornemann were not so different after all.

The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor by Cameron McCabe (Ernest Borneman) is published this month as a Picador Classic. To order a copy for 7.37 (RRP 8.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over 10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of 1.99.