Why the prissy reaction to Ferrante being unmasked? | Catherine Bennett

The latest literary outcry might suggest that readers are rarely interested in the novelist. History disagrees.

The first time that someone urged me to read Elena Ferrante, he mentioned her anonymity, along with her evocation of Naples, and her peerless representation of womens friendships, as among her most impressive qualities. This was in 2013, shortly after the critic James Wood had introduced Ferrante to readers of the New Yorker, in an essay that dwelt on her anonymity. Compared with Ferrante, Wood wrote, Thomas Pynchon is a publicity profligate.

A few things were known about the writer, thanks to Ferrantes generosity with written interviews, which routinely feature her anonymity. She grew up in Naples. She had a classics degree. She believed books should stand alone. Wood quoted a letter to her publisher, from 1991. I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they wont.

Enough of her readers now appear to share this austere analysis to justify a thorough rethink, in the media, of its coverage of novelists. No one really wanted to know the identity of Elena Ferrante, wrote Frances Wilson, in the Times Literary Supplement. In which case, maybe people dont, really, want to know about John le Carrs dad or the latest revelations about Elizabeth Jane Howard. Were above all that. Lets restore authentic centrality to the books themselves, Ferrante says.

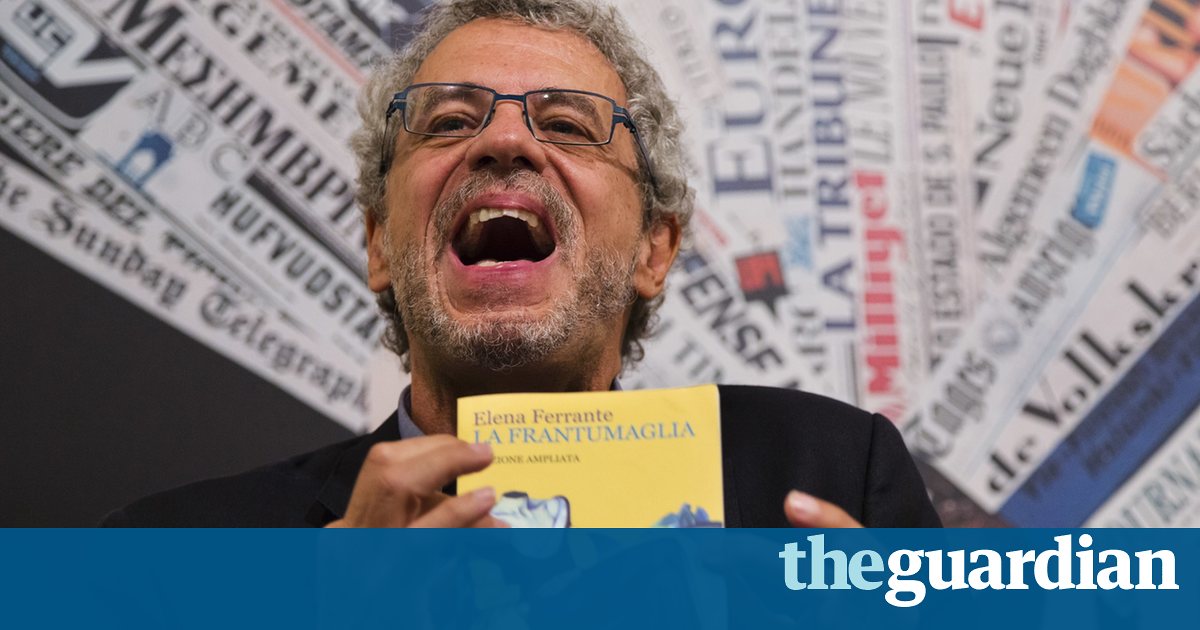

Mercifully for her publisher, Ferrantes books did find many thousands of readers, after which speculation about her identity intensified, even among admirers of her work. Wood, for example, mentioned a rumour about an Italian novelist, Domenico Starnone. He guessed at confessional reasons for her reticence, such as only confirmed her honesty. As soon as you read her fiction, Ferrantes restraint seems wisely self-protective.

Theres an echo of the conjecture that followed the publication of Jane Eyre, under the name Currer Bell. Who, indeed, but a woman, wrote one reviewer, could have ventured, with the smallest prospect of success, to fill three octavo volumes with the history of a womans heart?

The earlier review is quoted in a brilliant study by John Mullan, Anonymity: A Secret History of English Literature, in which context Ferrantes reticence and the avid response to it look far more like a return to literary convention than a rebuke to celebrity culture. As with Charlotte Bront, it was a matter of time, given the sales and adulation, before Elena Ferrante was identified. Following years of false starts, a reporter, Claudio Gatti, now exposes his suspect, in the manner of a police sergeant, as the Roman-based translator, Anita Raja. That Raja is married to Starnone is unlikely to end speculation about his involvement. As for Gatti, his reward, to date, has been sustained abuse. A British journalist proposed him as the most despised Italian on the planet and said he deserved to be bashed on the head, Ukip style, with a copy of My Brilliant Friend. The TLS editor, Stig Abell, protested that exposure had been achieved in the beastliest sort of way, involving money, as opposed to via the more agreeable, practical criticism. If only Gatti had been nicer, less Brexity, or better still, a woman. Abell is not alone in recoiling from a painfully gendered pursuit, of a woman who told the Financial Timess Liz Jobey: Male power, whether violently or delicately imposed, is still bent on subordinating us.

While the wretched Gatti is excoriated, anyone who shares his interest might as well, you gather, admit to a sneaking respect for Mazher Mahmood. The Booker prize winner Marlon James wrote on Facebook:, Seriously though, who is this NYRB [New York Review of Books]Elena Ferrante article for? What kind of person supports this shit and cared to find out?

OK, this kind. Im glad we know who wrote Jane Eyre and where she lived. And Im curious about Ferrante. Not merely because I belong to the same, debased trade as Gatti and do not share my friends enthusiasm for the novelist. Despite dogged attempts to enjoy Ferrante and to suppress conjecture about an oddly male glint, in some scenes I find Neapolitan novels fiction (the interviews are great) much as I did the magic realism of the 80s: lurid and prolix. It came as no surprise to find Salman Rushdie posting in Ferrantes support, notwithstanding his own generous offering, to inquisitive readers, of Joseph Anton, in which true-life romances are thrillingly explored.

But individual taste has no bearing on the principle that Elena Ferrante had a right to concealment. Whether she could reasonably expect full compliance, once she was revered and famous, sole cause of a tourism spike in Naples, is a different matter. JK Rowling, discussing her own outing as the detective writer Robert Galbraith, sounded resigned. I always knew if the books had any success, it would become harder and harder to remain anonymous because, quite reasonably, people would say, well, I would like to interview him or ask him some questions.

In that respect people are unchanged since they enjoyed guessing as they were sometimes intended to about the authorship, among others, of The Rape of the Lock, Gullivers Travels, Joseph Andrews, Pride and Prejudice, Ivanhoe, Frankenstein, Evelina, Mary Barton, Middlemarch, Alices Adventures in Wonderland, Father and Son, The Bell Jar, The Diaries of Jane Somers. A good proportion of what is now English literature, John Mullan writes, consists of works first published, like The Rape of the Lock, without their authors names.

Seriously, again to quote Marlon James, what kind of person supports this shit and cared to find out? Might they not be Ferrantes admirers? In his time, Thackeray was not above biographical speculation. I have been exceedingly moved and pleased by Jane Eyre. It is a womans writing, but whose? The English reading world, Elizabeth Gaskell wrote in her biography of Bront, was in a ferment to discover the unknown author.

Insisting on the gendered aspect of the Ferrante outrage, some have argued, not entirely unlike women who defend the burqa, that Gatti violated a self-effacement that is peculiarly womanly. If so and that behaviour did not originate with patriarchal restrictions on female writers there is, still, the consolation that the public knows almost as little about Ferrante, unveiled, as it did before. As intended, her books prospered under anonymity, they speak for themselves and no loyal reader will care if she wasnt raised in Naples, a disclosure that only accords with Ferrante, in Vanity Fair, on the centrality of the work.

For the tiny number of Ferrante-resistant readers, the violence of last weeks response may be as interesting as the unmasking. Whats this sudden consensus, among eager consumers of author interviews and confessions, from regular participants in literary festivals and talks, that a decent reader is interested only in texts? Should publishers accordingly trim, if such a thing were possible, their publicity budgets? Or does that strange phenomenon Ferrante fever account for an anti-biographical fury that remained dormant during the exposures, respectively, of Belle de Jour, JK Rowling and Banksy? True, Ferrante threatened never to publish again. But that was as the novelist raised in Naples.